Executive Corner – Do Bad Bosses “Raise” Bad Bosses?

Michael Clegg | 12/13/2023

Do bad bosses “raise” bad bosses? Or are those toxic behaviors from the nature of the leader’s personality?

It’s Nature vs. Nurture in the workplace.

Toxic bosses cast long shadows that extend far beyond personal well-being. The ramifications ripple through organizations, contributing to lowered morale, diminished well-being, and increased unhealthy conflict.

Most of us have witnessed or experienced a bad boss in our careers. It’s not a fun experience.

Stress levels are high.

You feel like you’re walking on eggshells.

No one feels like they can voice their opinions.

On the other hand, Good bosses can have bad boss tendencies, especially regarding unspoken expectations. Several months ago, I led our Leadership meeting and tasked the team with a project to create new metrics for our sales staff based on our goals. I wanted them to develop those metrics without my opinion or influence. I thought I was giving them an opportunity to lead from the front.

After a few weeks and nothing back from them, I asked, “Where are we on our new metrics project?” I had five people looking back at me with blank stares. “Why do you all look confused? What am I missing?” They didn’t realize I had officially tasked them with this project. They thought we were discussing the project—a brainstorming session. I thought I was being clear that I wanted them to take this and run. I typically pass on a lot of autonomy. This was a classic case of “Unspoken Expectations.” The challenge is I didn’t confirm that they understood the assignment, and I didn’t give them a “BY WHEN,” which is the deadline.

At this moment, I took the opportunity to reset the stage. One of the blind spots I am working on is my lack of clarity. My team knows this because I’m vocal about this blind spot. That’s why I reminded them that I expect them to point out when I’m unclear. We cost ourselves three weeks on this project because of my unspoken expectations. I was the bottleneck they were waiting on, yet I was waiting on them. I consider myself a good boss with a team that thrives on Psychological Safety. Even so, they didn’t speak up. It was a great opportunity to remind them why I trusted them and needed their help, ensuring I was clear.

So that poses the question: Where do bad bosses come from, and why do good bosses still sometimes have bad boss tendencies?

While previous research underscores the “trickle-down” effect of leader behaviors on subordinates, a critical question looms: Why do some abused supervisors perpetuate abuse while others break the cycle?

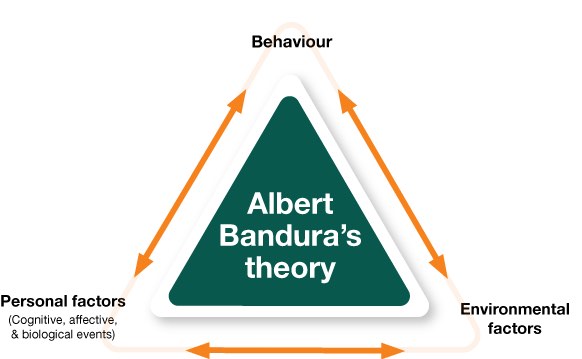

A social cognitive theory by Psychologist Albert Bandura suggests that behavior is learned from role models. However, not all individuals conform to observed behavior. Studies in developmental psychology suggest that a different process called disidentification motivates some to be the exact opposite. In other words, disidentification happens when people observe behavior, process it as bad, unethical, or something they don’t want to model and form their behavior to model the opposite. For example, when someone recognizes that their boss isn’t exhibiting behavior that they agree with, once that person becomes a leader, they use their former boss as an example of what NOT to be. Another example of disidentification can be placed in situations where children vow to break the cycle of abuse learned from their parents.

This theory was used to conduct a study with 288 participants taking on the supervisor role in a café scenario. In this study, some of whom this fictional manager mistreated, while others weren’t. The results showed that those who distanced themselves and disidentified with this behavior exhibited more ethical leadership than those who weren’t mistreated, showing that poor leadership might lead to better leaders in the future. Similarly, a real-world application in India, surveying 500 employees and leaders, solidified the connection: abusive behavior led to disidentification, notably among supervisors with a strong moral identity.

In my first job, I had a bad boss. He was what we would call today a command-and-control leader. He followed the “don’t do as I do, do as I say” methodology. He constantly berated his employees for lack of production. He humiliated us if we asked a question to which he thought we should know the answer. Turnover was high.

I stayed longer than I should have. I stayed because I got to take on more responsibility and I learned what a bad boss looked like. As I took on more responsibility, my new team often commented that they wished I was the Director and not Jeff. I saw firsthand what a command-and-control style leader was lacking.

There was no empathy.

No relationships.

No safety to ask questions or to try new ways of working.

It was a very cold and tough environment, which is why turnover was high. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was in the process of disidentification or in other words, learning how to NOT lead.

For organizations, the message is clear: breaking the cycle requires careful selection of supervisors with strong moral identities or actively strengthening the moral identities of existing managers. Strategies such as reminders of organizational or professional standards can contribute to creating a healthier workplace culture. Leaders experiencing abuse should take solace in the fact that their boss’s style does not define them. Instead, they can view the experience as an opportunity for growth, transforming a challenging chapter into a lesson on how not to lead a team.

As we navigate the shadows cast by toxic leadership, there is hope and agency in understanding that the cycle of abuse is not inevitable. By leveraging insights from diverse fields, individuals and organizations can foster environments that break free from the destructive patterns of abusive supervision. In this journey, recognition, disidentification, and a commitment to ethical leadership emerge as beacons guiding us toward workplaces marked by trust, respect, and growth.